BBC

BBCThe climb from the main road to the home of 79-year-old Matlohang Moloi is steep, through the mountains that make Lesotho one of the highest countries in the world.

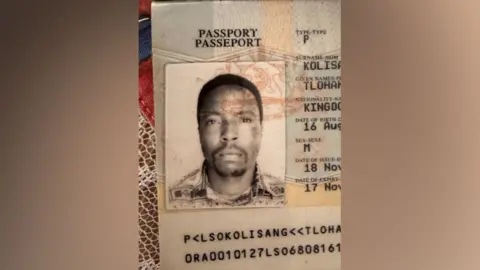

The mother of 10 welcomes me into her lovely home, showing me photos of her large family. I am here to talk about one of her children, her firstborn, Tlohang.

At 38, he has become part of a grim statistic. Lesotho, the kingdom in the sky, is home to the highest suicide rate in the world.

“Tlohang was a good son. He told me about his mental health issues,” says Ms Moloi.

“Even that day he took his own life, he came to me and said, ‘Mom, one day you’re going to hear that I took my own life.’

“His death hurt me a lot. I really wish he could have explained in more detail what was troubling him in his mind. He was worried that if he told people, they would think he was a weak person who couldn’t solve his problems.”

According to the World Health Organization, 87.5 people per 100,000 population in Lesotho take their own lives each year.

In contrast, this figure is more than double that of the next country on the list, Guyana in South America, where the figure is just over 40.

It is also nearly 10 times higher than the global average of nine suicides per 100,000 people.

This is a statistic that NGOs, like HelpLesotho, are determined to change by equipping young people with the skills to manage their mental health.

In the town of Hlotse, about two hours’ drive from the capital Maseru, I attend one of the regular group therapy sessions for young women, run by social worker Lineo Raphoka.

“People think it’s against our African principles, our cultural experiences, our spirituality as Africans and as a community in general,” Patience, 24, tells the group.

“But we’re also avoiding the fact that it’s happening. I speak from a perspective where I’ve lost three friends to suicide, I’ve personally attempted it.”

Everyone here has had suicidal thoughts or knows someone who has.

Ntsoaki, 35, becomes emotional as he tells the group the story of being raped in hospital.

“The doctor told me I was too attractive. Then he pulled out a gun and told me he wanted to have sex with me, and if I didn’t he would kill me.

“Every time I committed suicide, I always thought it was the only solution. I couldn’t do it, I didn’t have the strength to do it. The only thing that kept me moving or alive were the faces of my brothers. They think I’m strong, but I’m weak.”

The group reassures her that she is strong in sharing her feelings.

At the end of the session, all the women chat and smile, saying they felt better after sharing their stories.

The reasons why people take their own lives are often complex and it is difficult to isolate a single cause.

Despite this, Ms Raphoka says she sees patterns that explain why Lesotho has such a high suicide rate.

“Mostly they go through situations like rape, unemployment, loss due to death. They abuse drugs and alcohol.”

According to a 2022 World Population Review report, 86% of women in Lesotho have experienced gender-based violence.

Meanwhile, according to the World Bank, two out of five young people are neither employed nor educated.

“They don’t get enough support from their families, friends or whatever kind of relationship they’re in,” Ms Raphoka continues.

It’s something you hear a lot in Lesotho. People repeatedly say they don’t feel comfortable talking about their mental health, and that others might judge them.

One evening, sitting in a bar in Hlotse, where the male clientele is drinking local beer and chatting about politics while football matches are on TV, I shift the conversation to the topic of mental health.

“We talk about it, we say let’s open up,” Khosi Mpiti tells me.

Some are afraid that if they reveal too much they might be the subject of gossip. Despite this, she says things are improving.

“As a group [of friends] we are very supportive. If I have a problem I tell the group and we support each other.”

However, when people seek help, they are faced with a struggling public health system.

Last year, the country’s only psychiatric unit was criticized by the ombudsman, an official whose job is to protect public interests, because it had not had a psychiatrist since 2017.

He also highlighted widespread abuses, including “living conditions that violate human rights.”

Previously, there was not even a national mental health policy to address the crisis, although the government, elected in October 2022, says it is in the process of developing one.

“Mental health has become a pandemic,” admits Mokhothu Makhalanyane, a parliamentarian who heads a parliamentary committee that deals with health issues.

“We are ensuring that advocacy is scaled up, from primary schools to secondary schools, to places where young people gather, such as football tournaments,” he told the BBC.

“The policy will also be specific in terms of treatment and will allow those affected to access rehabilitation.”

He also says that Lesotho can learn a lot from its fight against HIV/AIDS.

In 2016, it became the first country to introduce a “test-and-treat” strategy, meaning people can start treatment as soon as they are diagnosed. Infection rates have steadily declined.

“The experience we’ve had is that speaking out, without blaming or criticizing people for their situation, has helped change things.”

Back in the mountains, Mrs. Moloi takes a short walk to tend to Tlohang’s tomb.

His final resting place is a land with a breathtaking view, dotted with streams, vegetation and small houses.

Ms Moloi is one of many people living in Lesotho who are dealing with the grief of death by suicide.

As we take in the view, he says he has a message for those in the same mental situation as his son.

“I would tell people that taking your life is never a solution. What you have to do is talk to the people around you so they can help you.”

If you have been touched by the issues described in this story and are experiencing distress or despair and need support, you may want to talk to a healthcare professional or an organization that offers support.

In the UK support is available via BBC Action LineDetails of support available in many countries can be found at Friends all over the world.

Other BBC articles on Lesotho:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC