BBC

BBC As Martina Canchi Nate walks through the Bolivian jungle, surrounded by red butterflies, we have to ask her to stop: our team can’t keep up with her.

His ID says he is 84 years old, but within 10 minutes he digs up three yucca trees to extract the tubers from their roots and, with just two swipes of his knife, fells a plane tree.

He loads a huge bunch of fruit onto his shoulders and begins walking home from his chaco, the plot of land where he grows cassava, corn, plantains and rice.

Martina is one of 16,000 Tsimanes (pronounced “chee-ma-nai”), a semi-nomadic indigenous community living deep in the Amazon rainforest, 600 km (375 miles) north of Bolivia’s largest city, La Paz.

His vigor is not unusual for Tsimanes his age. Scientists have concluded that the group has the healthiest arteries ever studied and that their brains age more slowly than those of people in North America, Europe and elsewhere.

The Tsimanes are a rarity. They are one of the last peoples on the planet to live a full subsistence lifestyle of hunting, gathering, and farming. The group is also large enough to provide a sizable scientific sample, and researchers, led by anthropologist Hillard Kaplan of the University of New Mexico, have been studying them for two decades.

The Tsimanes are constantly active: hunting animals, planting food, and weaving roofs.

Less than 10% of their daytime hours are spent in sedentary activities, compared to 54% for industrial populations. An average hunt, for example, lasts more than eight hours and covers 18 km.

They live on the Maniqui River, about 100 km by boat from the nearest town, and have had little access to processed foods, alcohol and cigarettes.

Researchers found that only 14 percent of their calories come from fat, compared to 34 percent in the U.S. Their foods are high in fiber, and 72 percent of their calories come from carbohydrates, compared to 52 percent in the U.S.

Protein comes from the animals they hunt, such as birds, monkeys, and fish. When it comes to cooking, traditionally, there is no frying.

Michael Gurven

Michael GurvenThe initial work of Prof. Kaplan and his colleague, Michael Gurven of the University of California, Santa Barbara, was anthropological. But they noted that the elderly Tsimanes showed no signs of typical old-age diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or heart problems.

Then a study published in 2013 caught their attention. A team led by American cardiologist Randall C Thompson used CT scanning to examine 137 mummies from the ancient Egyptian, Inca, and Unangan civilizations.

As we age, a buildup of fat, cholesterol, and other substances can cause our arteries to thicken or harden, causing atherosclerosis. They found signs of this in 47 of the mummies, challenging the idea that it’s caused by modern lifestyles.

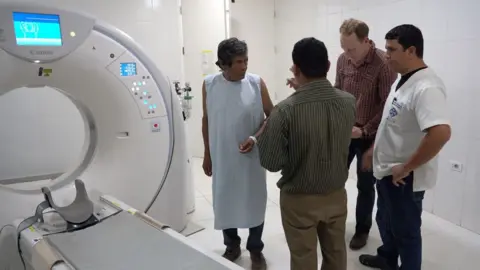

The two research teams joined forces and performed CT scans on 705 Tsimanes over the age of 40, looking for coronary artery calcium (CAC), a sign of clogged blood vessels and risk of heart attack.

Their study, first published in Tthe Lancet in 2017showed that 65% of Tsimanes over age 75 had no CAC. In comparison, most Americans that age (80%) have signs of it.

As Kaplan says: “The arteries of a 75-year-old Tsimane are more similar to those of a 50-year-old American.”

A second phase, published in 2023 Writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, they found that older Tsimanes had up to 70 percent less brain atrophy than people of the same age in industrialized countries such as the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States.

“We have not found any cases of Alzheimer’s in the entire adult population: this is remarkable,” says Bolivian doctor Daniel Eid Rodríguez, medical coordinator of the researchers.

However, calculating the age of the Tsimanes is not an exact science. Some have difficulty counting because they have not learned numbers well. They told us that they are guided by the records of Christian missions in the area or how long they have known each other. Scientists make calculations based on the ages of a person’s children.

According to their records, Hilda is 81 years old, but she says her family recently killed a pig to celebrate her “100th birthday or something.”

Juan, who says he is 78 years old, takes us hunting. He has dark hair, lively eyes, and strong, steady hands. We watch him chase a small taitetú, a hairy wild pig, that manages to scuttle through the foliage and escape.

He admits he feels his age: “The hardest thing now is my body. I don’t walk much anymore… it will take two days at most.”

Martina agrees. Tsimane women are known for weaving roofs with jatata, a plant that grows deep in the jungle. To find it, Martina has to walk three hours there and three hours back, carrying branches on her back.

“I do it once or twice a month, although it’s more difficult for me now,” she says.

Many Tsimanes never reach old age, however. When the study began, their average life expectancy was just 45 years; it has now risen to 50.

At the clinic where the tests are performed, Dr. Eid asks the elderly women about their families as they prepare for the visit.

Counting on her fingers, one woman sadly says she has had six children, five of whom have died. Another says she has had 12, four of whom have died – yet another says she has nine children still alive, but three more have died.

“These people who reach the age of 80 are the ones who have managed to survive a childhood full of diseases and infections,” says Dr. Eid.

Researchers believe that all Tsimanes experienced some type of parasitic or worm infection during their lives. They also found high levels of pathogens and inflammation, suggesting that the Tsimanes’ bodies were constantly fighting off infections.

This led them to wonder whether these early infections might be another factor, besides diet and exercise, underlying the health of older Tsimanes.

However, the community’s lifestyle is changing.

Juan says he hasn’t been able to hunt a large enough animal in months. A series of forest fires in late 2023 destroyed nearly two million hectares of jungle and forest.

“The fire caused the animals to leave,” he says.

He has now started raising cattle and shows us four beef cattle that he hopes will provide protein for the family later this year.

Dr. Eid says the use of boats with outboard motors, known as peque-peque, is also bringing about change. It makes markets easier to reach, giving the Tsimane access to foods such as sugar, flour and oil.

And he points out that this means they are rowing less than before, “one of the most physically demanding activities.”

Twenty years ago, there were almost no cases of diabetes. Now they are starting to appear, while cholesterol levels have started to rise even among the younger population, researchers have found.

“Any small change in their habits ends up impacting these health indicators,” says Dr. Eid.

And the researchers themselves have made an impact over the course of their 20 years of involvement, organizing better access to health care for the Tsimanes, from cataract surgeries to treatment for broken bones and snakebites.

But for Hilda, old age is not something to be taken too seriously. “I’m not afraid of dying,” she laughs, “because they’ll bury me and I’ll just be there… very still.”