BBC

BBCThe Middle East is in turmoil. International diplomacy is in overdrive. And for once, many in Israel, Lebanon, and Iran have something in common: a war of nerves.

They worry and wait to see what might happen next. It seems like the entire region is holding its breath.

Is this the slide into all-out regional war? Can a ceasefire be wrested from the ruins of Gaza? How will Iran and its proxy militia Hezbollah exact revenge on Israel for the back-to-back assassinations in Beirut and Tehran? Will they heed calls for restraint?

In Lebanon, the stifling heat of summer is covered with a layer of anxiety.

Heart-stopping sonic booms interrupt the hum of traffic in Beirut as Israeli warplanes break the sound barrier in the skies above.

Many foreign nationals have left, following the advice of their governments. Many Lebanese have also fled.

Others can’t get enough of it, like the thirty-year-old chef at a trendy bar (Beirut has too many to count). She’s tattooed and spontaneous, but prefers not to be named.

“Living in Beirut is like being in a toxic relationship that you can’t get out of,” she tells me.

“I am emotionally attached. I have relatives abroad and I could leave, but I don’t want to. We live day by day. And we joke about the situation.”

In the next breath he admits that business has suffered and that he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. “It’s like a cold war for us,” he says. He expects a hotter war, but hopes it will be short.

EPA

EPAInternational mediators are crisscrossing the region, working overtime to prevent a wider conflict. Among them is U.S. envoy Amos Hochstein.

“We continue to believe that a diplomatic resolution is achievable,” he said, “because we continue to believe that no one really wants a full-scale war between Lebanon and Israel.”

He said this on Wednesday in Beirut, after meeting a close ally of Hezbollah, the speaker of the Parliament Nabih Berry.

When asked by a reporter whether the war could have been avoided, Mr. Hochstein replied, “I hope so, I think so.” But he added that the more time passes, the greater the chances of accidents and mistakes.

News

NewsThe last time Israel and Hezbollah went to war, in 2006, it lasted six weeks and caused heavy damage and loss of life in Lebanon. More than 1,000 Lebanese civilians were killed, along with about 200 Hezbollah fighters. Of the 160 Israelis killed, most were soldiers.

All sides agree that a new war would be far more deadly and destructive.

And many here in Lebanon agree that the country cannot afford it. The economy is paralyzed and the political system is dysfunctional. The government can’t even keep the lights on.

“I hope there won’t be a war,” says Hiba Maslkhi. “Lebanon won’t be able to cope.”

We meet the 35-year-old in a tracksuit on a slipway on the Beirut waterfront. She is focused on the Mediterranean, fishing rod in hand.

“I hope that wiser heads will prevail,” he says, “and that we will be able to control the escalation so that things do not get out of control.”

He takes every sonic boom personally. “If I hear one, I start to panic and wonder if [Israeli forces] They hit near my house or bombed the airport.”

Hiba, who makes a living selling perfume, says Lebanon has suffered enough already.

“Ten months is a long time to be psychologically destroyed, hiding in our homes,” she says. “We are afraid to start businesses to earn some money because we think war could be around the corner.”

The current phase of the conflict began last October, when Hamas gunmen stormed into the Gaza Strip and killed around 1,200 people in southern Israel, mostly civilians.

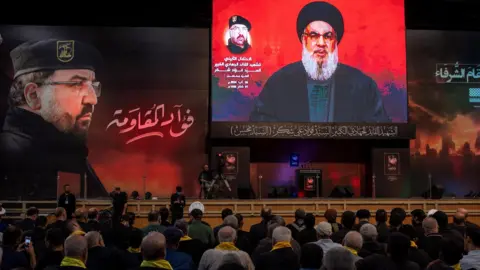

Hezbollah soon joined in, firing from Lebanon toward Israel. The Shiite Islamist armed group and political party, classified as a terrorist organization by Britain and the United States, said it was acting in support of the Palestinian people.

Since October, Hezbollah and Israel have exchanged fire, forcing tens of thousands of people to flee on both sides of the shared border and killing more than 500 people in Lebanon, most of them fighters. Israeli officials say 40 people have been killed there, including 26 soldiers.

Fears of a wider conflict emerged in late July, when an Israeli strike in Beirut killed a high-ranking Hezbollah commander.

Israel held him responsible for the killing of 12 children in a rocket attack on the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights in Syria.

News

NewsIt is already all-out war in Gaza, where Israel has killed nearly 40,000 Palestinians at the latest count, according to data from the Hamas-run Health Ministry, figures the World Health Organization considers credible.

Gaza is Ayman Sakr’s main concern. He fishes with Heba, but their views are very different.

The 50-year-old taxi driver insists that if all-out war breaks out, Lebanon will handle it. “There is some concern, but we can handle it,” he tells us. “We will ultimately defend ourselves. If we die, that’s OK.”

He was quick to pay tribute to the hundreds of Hezbollah fighters killed by Israel and to the armed group’s leader.

“I salute the resistance and those who were martyred from the bottom of my heart,” he says, “and I salute Hassan Nasrallah who made us and all Arabs proud. Everyone is worried about Israel, what about the 39,000 people Israel killed?”

Ayman, a father of five, says the horror in Gaza is undeniable, but it is being ignored.

“The whole world sees children, women and old people being massacred every day in front of the cameras and no one notices,” he says. “People’s children are being killed before their eyes. Where is the world? Those who remain silent are complicit.”

Hiba still hopes that a full-scale war can be avoided.

“No one has the right to kill anyone,” he says, “neither organizations, nor parties, nor militias. I hope that the new generation will be wiser than the one that preceded it.”